The Little Windjammer That Could

(Click on any photo to enlarge)

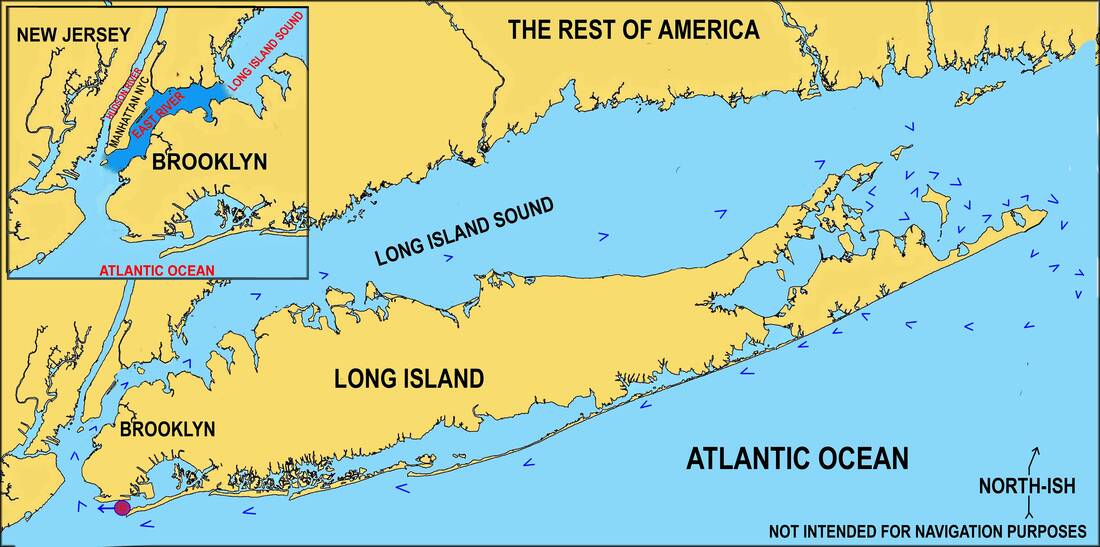

Captain Levi Sprat on a calm day rows off to the

krill grounds.

Captain Levi Sprat on a calm day rows off to the

krill grounds.

Part 1 – Captain Sprat and the origins of a small schooner

The schooner Meteor (pronounced: mē-at~əater) came from the ancestral mudflats of Captain Levi Sprat, Maine clam fisherman. It had always been his dream to someday command his own schooner. In 1922 that dream became reality. During an extremely low tide he discovered the preserved remains of a small quogue, a type of small two-master built for jelly fishing by the early settlers.

Captain Sprat, seeing this discovery as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, dug the quogue from the mud and, after an extensive refit, set out to enter his boat in the lucrative krill trade.

Levi Sprat, in honor of his father, named his small schooner Meteor. As his old man, by coincidence also a clam digger, used to tell, “Son, even if you don’t see a meteor’s streak you can still hear it hit the mud,” while going on to explain that even after it landed it was still possible to make a wish. Unfortunately, one summer’s dawn the elder Sprat didn’t see or hear the meteor that struck him down. The younger Sprat was never told the truth of his father’s untimely demise and the boy grew up believing in wishes...

With his new vessel Captain Sprat set out to corner the krill market.

His remarkable success is well documented, as noted in the captain’s log of the whaling bark the Morning After:

“June the 19th 1923. With the schooner Meteor alongside we took aboard one hundred hoggers of krill.[1] That stuff is expensive... sure wish Captain Sprat hadn’t cornered the market.”

Sprat’s schooner was a common sight on the krill grounds as the lone skipper worked those dangerous shoals east of the Western Shoals. Even in the harshest conditions, the Meteor could be seen, her tiller lashed with Captain Sprat tonging the beds for his precious catch. Krilling was honest, backbreaking work but Levi Sprat was an honest, backbreaking man.

It was in 1929 when two events conspired to change the course of the Meteor and her master. The first was that Captain Sprat, after many years of grueling work, finally finished reading Moby Dick. Oddly, he found himself sympathizing with the whale and not Ahab. Additionally, he suspected Ishmael was something of a sissy... and to Sprat, who came from generations of New England stock, that just didn’t sit well. Suddenly the skipper was no longer enamored with the whole notion of whaling... or whalers for that matter. Still, he had bills to pay, so Sprat kept krilling.

Then came the second drumbeat of fate when, in October of that same year, the stock market crashed. The economy dove like a hungry fish hawk... wings back and straight down. Captain Sprat didn’t hear the bad news right away. Instead he was battling a fierce gale as the Meteor was blown ever northward. When the storm finally abated, man and schooner made for the nearest port, Halifax. There he found refuge at McGerkin’s Wharf & Bait & Sons & Co. It was dockside that Captain Sprat heard of his country’s economic crash and realized bad times were ahead.

[1] A single hogger is equivalent to seventeen mason jars.

The schooner Meteor (pronounced: mē-at~əater) came from the ancestral mudflats of Captain Levi Sprat, Maine clam fisherman. It had always been his dream to someday command his own schooner. In 1922 that dream became reality. During an extremely low tide he discovered the preserved remains of a small quogue, a type of small two-master built for jelly fishing by the early settlers.

Captain Sprat, seeing this discovery as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, dug the quogue from the mud and, after an extensive refit, set out to enter his boat in the lucrative krill trade.

Levi Sprat, in honor of his father, named his small schooner Meteor. As his old man, by coincidence also a clam digger, used to tell, “Son, even if you don’t see a meteor’s streak you can still hear it hit the mud,” while going on to explain that even after it landed it was still possible to make a wish. Unfortunately, one summer’s dawn the elder Sprat didn’t see or hear the meteor that struck him down. The younger Sprat was never told the truth of his father’s untimely demise and the boy grew up believing in wishes...

With his new vessel Captain Sprat set out to corner the krill market.

His remarkable success is well documented, as noted in the captain’s log of the whaling bark the Morning After:

“June the 19th 1923. With the schooner Meteor alongside we took aboard one hundred hoggers of krill.[1] That stuff is expensive... sure wish Captain Sprat hadn’t cornered the market.”

Sprat’s schooner was a common sight on the krill grounds as the lone skipper worked those dangerous shoals east of the Western Shoals. Even in the harshest conditions, the Meteor could be seen, her tiller lashed with Captain Sprat tonging the beds for his precious catch. Krilling was honest, backbreaking work but Levi Sprat was an honest, backbreaking man.

It was in 1929 when two events conspired to change the course of the Meteor and her master. The first was that Captain Sprat, after many years of grueling work, finally finished reading Moby Dick. Oddly, he found himself sympathizing with the whale and not Ahab. Additionally, he suspected Ishmael was something of a sissy... and to Sprat, who came from generations of New England stock, that just didn’t sit well. Suddenly the skipper was no longer enamored with the whole notion of whaling... or whalers for that matter. Still, he had bills to pay, so Sprat kept krilling.

Then came the second drumbeat of fate when, in October of that same year, the stock market crashed. The economy dove like a hungry fish hawk... wings back and straight down. Captain Sprat didn’t hear the bad news right away. Instead he was battling a fierce gale as the Meteor was blown ever northward. When the storm finally abated, man and schooner made for the nearest port, Halifax. There he found refuge at McGerkin’s Wharf & Bait & Sons & Co. It was dockside that Captain Sprat heard of his country’s economic crash and realized bad times were ahead.

[1] A single hogger is equivalent to seventeen mason jars.

Newlyweds Captain Levi and Ethel Sprat set off on their honeymoon.

Newlyweds Captain Levi and Ethel Sprat set off on their honeymoon.

Part 2 — Hard times, a wedding and a mystery

With the economy in shambles Captain Sprat knew the Whaling Industry would suffer greatly. Already whale oil had been superseded by Texas Crude. However, a strong market remained for ambergris a rare waxy blob found in whale vomit and used in the manufacture of expensive perfumes for the very, very rich.[2] Come the depression, gone were the upper crust who could afford such luxuries and gone too was the eternal shout from the masthead, “Thar she pukes!”

But Captain Sprat was no stranger to hardship and sacrifice. When six the boy had been told his father had died from an infected clam bite. Without hesitation the youth had dropped out of first grade to support his mother and nine younger siblings.

Now dockside, just ahead of the Meteor, two hearty Canadian fishing schooners were hastily loading cases of booze. While Sprat watched them old man McGerkin came along and suggested Sprat should try a little bootlegging. But Sprat, a teetotaler, was too honest to engage in such an illicit trade. However, necessity is the mother of invention and finally Sprat thought of a legitimate way to profit from Prohibition.

A week later, the Meteor arrived in Boston. There, under the eyes of watchful customs inspectors, he offloaded fifty cases of generous three-ounce shot glasses. By nightfall Sprat’s novel cargo was sold.

Captain Sprat, as you might imagine, was already something of a local legend. He was a remnant of days gone by, known for single-handing the last vessel to krill under sail. Now his new venture was too delicious for the newspapers to resist. With all that publicity, each of Captain Sprat’s landings was greeted by throngs of well-wishing souvenir hunters.

Things were going swimmingly for Captain Sprat and the Meteor. For the first time in his life he was making good money and trips in his small Meteor were more like yacht outings than work.

In December 1933 the then-popular magazine Clam Shack, Boats and Inlets featured Captain Levi Sprat and the Meteor as their cover story. Man and schooner posed dockside with a genuine old time clam shack behind them. Though a nicely written piece, the story was quickly overshadowed by news of the repeal of Prohibition. Alcohol was suddenly legal again. Sprat’s trade in shot glasses was at an end.

For a time Captain Sprat tried to return to krilling but he was so much older by then that the work was no longer as agreeable as it once was. Thinking it time to reevaluate his situation, the aging captain sailed home to Maine. There he stashed the Meteor on the clam flats where first he found her and hoped for better times ahead. In an unexpected twist, they were.

At the age of eighty-two Levi Sprat became reacquainted with his boyhood sweetheart. Although there was an age difference between them, Sprat never let the notion that she was ten years his elder stand in the way. They were soon married. In preparation for the joyous event Sprat refloated and spruced up the Meteor. Following the ceremony the whole town turned out to see Levi and Ethel sail off on their honeymoon.

A year later the schooner was discovered offshore, wallowing in the swells with no one aboard. Below there was a warm, half-eaten meatloaf. With no sign of the newlyweds a Coast Guard cutter towed the drifting Meteor to port and an official inquiry was begun. There was much speculation and many opinions but in the end the mystery remained.

Over the years there were a number of Levi and Ethel sightings. The first was by a hotel clerk in Secaucus, New Jersey, the second reported by a lifeguard in the Florida Panhandle and, by one almost credible account, the prime minister of San Esposa swore the couple had, on several occasions, supped with him at the palace.

Ultimately none of the reports were ever substantiated and the story of Levi and Ethel’s disappearance remains a mystery to this day.

[2] Due to space requirements the word very has been kept to the minimum number required.

With the economy in shambles Captain Sprat knew the Whaling Industry would suffer greatly. Already whale oil had been superseded by Texas Crude. However, a strong market remained for ambergris a rare waxy blob found in whale vomit and used in the manufacture of expensive perfumes for the very, very rich.[2] Come the depression, gone were the upper crust who could afford such luxuries and gone too was the eternal shout from the masthead, “Thar she pukes!”

But Captain Sprat was no stranger to hardship and sacrifice. When six the boy had been told his father had died from an infected clam bite. Without hesitation the youth had dropped out of first grade to support his mother and nine younger siblings.

Now dockside, just ahead of the Meteor, two hearty Canadian fishing schooners were hastily loading cases of booze. While Sprat watched them old man McGerkin came along and suggested Sprat should try a little bootlegging. But Sprat, a teetotaler, was too honest to engage in such an illicit trade. However, necessity is the mother of invention and finally Sprat thought of a legitimate way to profit from Prohibition.

A week later, the Meteor arrived in Boston. There, under the eyes of watchful customs inspectors, he offloaded fifty cases of generous three-ounce shot glasses. By nightfall Sprat’s novel cargo was sold.

Captain Sprat, as you might imagine, was already something of a local legend. He was a remnant of days gone by, known for single-handing the last vessel to krill under sail. Now his new venture was too delicious for the newspapers to resist. With all that publicity, each of Captain Sprat’s landings was greeted by throngs of well-wishing souvenir hunters.

Things were going swimmingly for Captain Sprat and the Meteor. For the first time in his life he was making good money and trips in his small Meteor were more like yacht outings than work.

In December 1933 the then-popular magazine Clam Shack, Boats and Inlets featured Captain Levi Sprat and the Meteor as their cover story. Man and schooner posed dockside with a genuine old time clam shack behind them. Though a nicely written piece, the story was quickly overshadowed by news of the repeal of Prohibition. Alcohol was suddenly legal again. Sprat’s trade in shot glasses was at an end.

For a time Captain Sprat tried to return to krilling but he was so much older by then that the work was no longer as agreeable as it once was. Thinking it time to reevaluate his situation, the aging captain sailed home to Maine. There he stashed the Meteor on the clam flats where first he found her and hoped for better times ahead. In an unexpected twist, they were.

At the age of eighty-two Levi Sprat became reacquainted with his boyhood sweetheart. Although there was an age difference between them, Sprat never let the notion that she was ten years his elder stand in the way. They were soon married. In preparation for the joyous event Sprat refloated and spruced up the Meteor. Following the ceremony the whole town turned out to see Levi and Ethel sail off on their honeymoon.

A year later the schooner was discovered offshore, wallowing in the swells with no one aboard. Below there was a warm, half-eaten meatloaf. With no sign of the newlyweds a Coast Guard cutter towed the drifting Meteor to port and an official inquiry was begun. There was much speculation and many opinions but in the end the mystery remained.

Over the years there were a number of Levi and Ethel sightings. The first was by a hotel clerk in Secaucus, New Jersey, the second reported by a lifeguard in the Florida Panhandle and, by one almost credible account, the prime minister of San Esposa swore the couple had, on several occasions, supped with him at the palace.

Ultimately none of the reports were ever substantiated and the story of Levi and Ethel’s disappearance remains a mystery to this day.

[2] Due to space requirements the word very has been kept to the minimum number required.

The Old Salt arrives in Boston aboard the Meteor following his famous attack on the German U-Boat

The Old Salt arrives in Boston aboard the Meteor following his famous attack on the German U-Boat

Part 3 — In service to the country

For many years the neglected Meteor languished at the Navy Pier in Boston. Sandwiched between two destroyers the placement turned out to be fortunate for the schooner. With large vessels on both sides she was sheltered the year the Hurricane of 1938 came through.[3]

For the longest time the schooner remained hidden from view. Her white paint, last spruced up for the wedding of Levi and Ethel, aged to dull gray, matching the warships around her.

It seemed as if the diminutive Meteor was just going to fade into oblivion. But then on December 7th 1941 the schooner experienced an unlikely stroke of luck. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and America was dragged into a war it had long avoided. Within days the Navy’s North Atlantic Fleet headed to sea. The only vessels left at the Navy Pier were a few picket boats and one diminutive, forgotten schooner.

During the First World War many sailing vessels had been employed by the Navy to patrol America’s shores. They could cruise silently while listening underwater for the approach of submarines. If discovered a radio warning would be issued. These once private yachts became a fleet of mystery ships, trading their glamorous paint and varnish for a coat of drab gray. The vessel’s crews were mostly comprised of volunteer yachtsmen who were not otherwise qualified for military service. Now, with the new war, fate determined the Meteor’s next remarkable course and a new improbable captain...

No one knew the man’s name. A hulking fixture along the waterfront, a solitary

ham-fisted wanderer most people preferred not to notice. His clothes were a sailor’s uniform of the old school, carefully restitched by hand along once threadbare seams. Except for two deep-set eyes, the man’s burly face was lost in a swirling fog of gray whiskers. Assumed to be homeless, the wandering recluse had been a fixture along the waterfront so long he could come and go as he pleased and not even the military police bothered with him. If by chance anyone had to refer to the old salt they simply called him the Old Salt.

Certainly no one suspected that this Old Salt had, for quite some time, been making his berth aboard the schooner Meteor. Nor could anyone imagine the Old Salt was fully alert to the world around him. Therefore, how could anyone suspect that the large supposedly homeless man, who spent his days murmuring to himself, was determined to live up to the uniform he had so proudly worn for decades and the oath he swore when first he put it on.

Eight weeks after war’s declaration the Old Salt, having patched the Meteor’s tired rigging and sails, took some discarded white paint and lettered with an even hand CGR2529 on the schooner’s bows. After marking the Meteor with “official” numbers the Old Salt scavenged a few stores and awaited a fair wind. It was early February when the Meteor’s new master sailed into the cold winter dusk.

With land out of sight the Meteor steadfastly patrolled the icy Atlantic. First bearing north, then south, then north again before heading south. The Old Salt kept at it, all the while alert for enemy subs. He spared nothing for personal comfort, ate the fish he caught and slept with an eye and an ear open. A lesser person would likely not have endured, but the Old Salt remained tough as cotter pins...

It was his twenty-third day on patrol when the Old Salt noted the appearance of an American ship a mile distant and steaming east. Many troop ships had passed him by so at first sighting this one was no different. Just another Liberty Ship, this time it was the F.A.O. Schwarz whose keel had been laid just two days prior.

Watching the distant ship the Old Salt suddenly sensed something was out of kilter. A strange vibration traveled through the sea, up the schooner’s keel, through her tiller, finally migrating into in the veteran sailor’s bones. Some large, invisible machinery was growing close...

And suddenly, seemingly yards away, a massive, angry submarine appeared, surfacing like Ahab’s whale. She was the German U-222 with her bow and torpedoes aimed directly at the slow-moving Schwarz.

Mumbling with excitement the Old Salt had little time to think. With instinct overtaking reason he instantly lashed the helm to lay his schooner alongside the deadly menace. Then, dashing below, he grabbed the only weapon he could find and, with a move most younger sailors wouldn’t dare, he leaped aboard the U-222. There, with a single blow, the Old Salt smashed the periscope’s lens to shards with nothing more than a half a stale, petrified meatloaf. Blinded, the U-boat was forced to hastily submerge.

The submarine dove so quickly the Old Salt suddenly found himself alone in the sea. With the Meteor beyond reach it looked as if he would drown but quick actions aboard the American ship turned the tide. A boat was quickly launched to the rescue and, post-haste, fished the drowning hero from the sea. When it was offered, the Old Salt would have no part of being taken aboard the Schwarz, expressing his preference with loud, profoundly incomprehensible, and possibly obscene mutters. The Old Salt’s protests didn’t stop until he was rowed back to and placed aboard the Meteor. Content once again, he hauled in the main sheet and hastened away.

On shore word of the Old Salt’s deed spread like talcum powder... It was, as the public perceived, an inspirational, selfless act by a venerable old American sailor. Eventually the Meatloaf Maneuver became part of Naval Academy training but, more immediately, served to inspire a generation of aging yachtsmen, motivating them to go to sea as the first line of defense for their beach houses.

And what of the Old Salt? He would have kept at his patrol indefinitely, but the War Department Film Liaison Unit dispatched a cutter with orders for the Meteor to return to port. Ever the patriot, the schooner’s master set a course for home.

The heroic Old Salt’s arrival at the Navy Pier was a public relations bonanza for the War Department. Cameras from all parts rolled and flashed as the befuddled sailor was presented with a brass key to the commissary bathroom[4]. But when the crowds dispersed and the Old Salt was hitting the head, the Meteor was lifted from the water and, still dripping, placed in a shipping container. Her destination: three thousand miles along the silver rails to Hollywood.

The Old Salt, without a vessel at his command, returned to wandering the waterfront. Though he never saw the little schooner again, his contribution to naval strategy remains to this day.

As to the Meteor, the Navy gave her to Piedmont Studios to be featured in series of films meant to inspire an America at war.

[3] There was another hurricane of ’38 in 1946 but by then the Meteor was thousands of miles away.

[4] The actual key was recently discovered during construction of the new tunnel along the Boston Waterfront. Historians confirmed the authenticity by the engraving above the blade stating, “DO NOT DUPLICATE.”

For many years the neglected Meteor languished at the Navy Pier in Boston. Sandwiched between two destroyers the placement turned out to be fortunate for the schooner. With large vessels on both sides she was sheltered the year the Hurricane of 1938 came through.[3]

For the longest time the schooner remained hidden from view. Her white paint, last spruced up for the wedding of Levi and Ethel, aged to dull gray, matching the warships around her.

It seemed as if the diminutive Meteor was just going to fade into oblivion. But then on December 7th 1941 the schooner experienced an unlikely stroke of luck. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and America was dragged into a war it had long avoided. Within days the Navy’s North Atlantic Fleet headed to sea. The only vessels left at the Navy Pier were a few picket boats and one diminutive, forgotten schooner.

During the First World War many sailing vessels had been employed by the Navy to patrol America’s shores. They could cruise silently while listening underwater for the approach of submarines. If discovered a radio warning would be issued. These once private yachts became a fleet of mystery ships, trading their glamorous paint and varnish for a coat of drab gray. The vessel’s crews were mostly comprised of volunteer yachtsmen who were not otherwise qualified for military service. Now, with the new war, fate determined the Meteor’s next remarkable course and a new improbable captain...

No one knew the man’s name. A hulking fixture along the waterfront, a solitary

ham-fisted wanderer most people preferred not to notice. His clothes were a sailor’s uniform of the old school, carefully restitched by hand along once threadbare seams. Except for two deep-set eyes, the man’s burly face was lost in a swirling fog of gray whiskers. Assumed to be homeless, the wandering recluse had been a fixture along the waterfront so long he could come and go as he pleased and not even the military police bothered with him. If by chance anyone had to refer to the old salt they simply called him the Old Salt.

Certainly no one suspected that this Old Salt had, for quite some time, been making his berth aboard the schooner Meteor. Nor could anyone imagine the Old Salt was fully alert to the world around him. Therefore, how could anyone suspect that the large supposedly homeless man, who spent his days murmuring to himself, was determined to live up to the uniform he had so proudly worn for decades and the oath he swore when first he put it on.

Eight weeks after war’s declaration the Old Salt, having patched the Meteor’s tired rigging and sails, took some discarded white paint and lettered with an even hand CGR2529 on the schooner’s bows. After marking the Meteor with “official” numbers the Old Salt scavenged a few stores and awaited a fair wind. It was early February when the Meteor’s new master sailed into the cold winter dusk.

With land out of sight the Meteor steadfastly patrolled the icy Atlantic. First bearing north, then south, then north again before heading south. The Old Salt kept at it, all the while alert for enemy subs. He spared nothing for personal comfort, ate the fish he caught and slept with an eye and an ear open. A lesser person would likely not have endured, but the Old Salt remained tough as cotter pins...

It was his twenty-third day on patrol when the Old Salt noted the appearance of an American ship a mile distant and steaming east. Many troop ships had passed him by so at first sighting this one was no different. Just another Liberty Ship, this time it was the F.A.O. Schwarz whose keel had been laid just two days prior.

Watching the distant ship the Old Salt suddenly sensed something was out of kilter. A strange vibration traveled through the sea, up the schooner’s keel, through her tiller, finally migrating into in the veteran sailor’s bones. Some large, invisible machinery was growing close...

And suddenly, seemingly yards away, a massive, angry submarine appeared, surfacing like Ahab’s whale. She was the German U-222 with her bow and torpedoes aimed directly at the slow-moving Schwarz.

Mumbling with excitement the Old Salt had little time to think. With instinct overtaking reason he instantly lashed the helm to lay his schooner alongside the deadly menace. Then, dashing below, he grabbed the only weapon he could find and, with a move most younger sailors wouldn’t dare, he leaped aboard the U-222. There, with a single blow, the Old Salt smashed the periscope’s lens to shards with nothing more than a half a stale, petrified meatloaf. Blinded, the U-boat was forced to hastily submerge.

The submarine dove so quickly the Old Salt suddenly found himself alone in the sea. With the Meteor beyond reach it looked as if he would drown but quick actions aboard the American ship turned the tide. A boat was quickly launched to the rescue and, post-haste, fished the drowning hero from the sea. When it was offered, the Old Salt would have no part of being taken aboard the Schwarz, expressing his preference with loud, profoundly incomprehensible, and possibly obscene mutters. The Old Salt’s protests didn’t stop until he was rowed back to and placed aboard the Meteor. Content once again, he hauled in the main sheet and hastened away.

On shore word of the Old Salt’s deed spread like talcum powder... It was, as the public perceived, an inspirational, selfless act by a venerable old American sailor. Eventually the Meatloaf Maneuver became part of Naval Academy training but, more immediately, served to inspire a generation of aging yachtsmen, motivating them to go to sea as the first line of defense for their beach houses.

And what of the Old Salt? He would have kept at his patrol indefinitely, but the War Department Film Liaison Unit dispatched a cutter with orders for the Meteor to return to port. Ever the patriot, the schooner’s master set a course for home.

The heroic Old Salt’s arrival at the Navy Pier was a public relations bonanza for the War Department. Cameras from all parts rolled and flashed as the befuddled sailor was presented with a brass key to the commissary bathroom[4]. But when the crowds dispersed and the Old Salt was hitting the head, the Meteor was lifted from the water and, still dripping, placed in a shipping container. Her destination: three thousand miles along the silver rails to Hollywood.

The Old Salt, without a vessel at his command, returned to wandering the waterfront. Though he never saw the little schooner again, his contribution to naval strategy remains to this day.

As to the Meteor, the Navy gave her to Piedmont Studios to be featured in series of films meant to inspire an America at war.

[3] There was another hurricane of ’38 in 1946 but by then the Meteor was thousands of miles away.

[4] The actual key was recently discovered during construction of the new tunnel along the Boston Waterfront. Historians confirmed the authenticity by the engraving above the blade stating, “DO NOT DUPLICATE.”

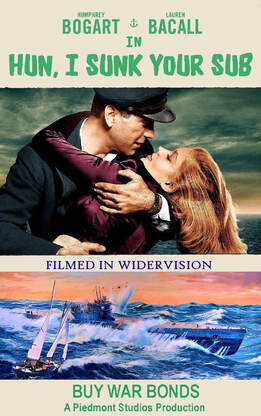

Original lobby card used to promote Hun, I Sunk Your Sub

Original lobby card used to promote Hun, I Sunk Your Sub

Part 4 — The Hollywood years

The Meteor’s first movie titled Hun, I Sunk Your Sub was a dramatic retelling of the Old Salt’s exploits. Many Hollywood actors vied for the hero’s role but it was heartthrob Humphrey Bogart who was cast as leading man, with Lauren Bacall as his romantic interest.

The storyline had the Old Salt rescue a beautiful American heiress from the lecherous hands of Commander Heimlich, a deviant who wanted nothing more than to make perfect Aryan children with the leading lady. Just in time the Old Salt rescued the girl before sinking the nefarious U-666 with a thrust of his meatloaf.[5] Eventually the handsome Old Salt and Penelope Remington sailed off, as the credits rolled, into a black-and-white sunset.

The next film took place in Hawaii. In Armada of One, the Meteor, as the sole survivor of the attack on Pearl Harbor, sailed off to block the Japanese Fleet in their attempt to withdraw. John Wayne, playing the schooner’s captain, became hoarse bellowing the iconic line, “Right of way, damn you! I’m under sail!” It was a classic test of wills against the Japanese admiral played by Jimmy Durante who was barely recognizable in his heavy eyeliner.

The tense standoff lasted two days[6] until, in a spectacular, fiery battle sequence, the American ship models arrived to defeat the cowardly Japanese ship models.

During that year’s Academy Awards it came as no surprise when the Meteor won Best Two-Masted Sailing Vessel Under Sixty -Five Feet In A Live Action Feature That Was Filmed In A Tank.

The third movie that the Meteor participated in was an animated short.

In it Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd formed an alliance to battle the Germans in what eventually became a classic. Weedle Biddy Skoona was conceived as an allegory, explaining to children the wartime alliance between the democratic United States and communist Russia.

Unfortunately before Weedle Biddy Skoona was completed, Germany surrendered, leaving the film’s release uncertain. The short remained in the can until the invention of television. Then, a with a quick redub, and Bugs redrawn wearing a dress, the cartoon became a staple on Saturday mornings where generations of young minds were alerted to the ever-present Soviet threat and, of course, the joys of cross dressing.

With the war over Hollywood delved into more modern themes, leaving the Meteor sidelined once again. She likely would have been scrapped but talks began of featuring the schooner in a Little Rascals revival. The first installment, Our Gang: Pirate Cove, might have been a great hit but Darla was pregnant again and Spanky was no longer cute. There were other issues, but the short of it was the project was dropped. Fortunately, it was that brief reprieve from the wrecking yard that prevented the Meteor’s ultimate demise.

[5] The special effects people had an impossible time piercing steel with half a meatloaf, so for filming an entire meatloaf was used.

[6] Two days in movie time, or roughly 48 minutes.

The Meteor’s first movie titled Hun, I Sunk Your Sub was a dramatic retelling of the Old Salt’s exploits. Many Hollywood actors vied for the hero’s role but it was heartthrob Humphrey Bogart who was cast as leading man, with Lauren Bacall as his romantic interest.

The storyline had the Old Salt rescue a beautiful American heiress from the lecherous hands of Commander Heimlich, a deviant who wanted nothing more than to make perfect Aryan children with the leading lady. Just in time the Old Salt rescued the girl before sinking the nefarious U-666 with a thrust of his meatloaf.[5] Eventually the handsome Old Salt and Penelope Remington sailed off, as the credits rolled, into a black-and-white sunset.

The next film took place in Hawaii. In Armada of One, the Meteor, as the sole survivor of the attack on Pearl Harbor, sailed off to block the Japanese Fleet in their attempt to withdraw. John Wayne, playing the schooner’s captain, became hoarse bellowing the iconic line, “Right of way, damn you! I’m under sail!” It was a classic test of wills against the Japanese admiral played by Jimmy Durante who was barely recognizable in his heavy eyeliner.

The tense standoff lasted two days[6] until, in a spectacular, fiery battle sequence, the American ship models arrived to defeat the cowardly Japanese ship models.

During that year’s Academy Awards it came as no surprise when the Meteor won Best Two-Masted Sailing Vessel Under Sixty -Five Feet In A Live Action Feature That Was Filmed In A Tank.

The third movie that the Meteor participated in was an animated short.

In it Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd formed an alliance to battle the Germans in what eventually became a classic. Weedle Biddy Skoona was conceived as an allegory, explaining to children the wartime alliance between the democratic United States and communist Russia.

Unfortunately before Weedle Biddy Skoona was completed, Germany surrendered, leaving the film’s release uncertain. The short remained in the can until the invention of television. Then, a with a quick redub, and Bugs redrawn wearing a dress, the cartoon became a staple on Saturday mornings where generations of young minds were alerted to the ever-present Soviet threat and, of course, the joys of cross dressing.

With the war over Hollywood delved into more modern themes, leaving the Meteor sidelined once again. She likely would have been scrapped but talks began of featuring the schooner in a Little Rascals revival. The first installment, Our Gang: Pirate Cove, might have been a great hit but Darla was pregnant again and Spanky was no longer cute. There were other issues, but the short of it was the project was dropped. Fortunately, it was that brief reprieve from the wrecking yard that prevented the Meteor’s ultimate demise.

[5] The special effects people had an impossible time piercing steel with half a meatloaf, so for filming an entire meatloaf was used.

[6] Two days in movie time, or roughly 48 minutes.

The schooner Meteor as a tourist attraction at Antony's Pier 7

The schooner Meteor as a tourist attraction at Antony's Pier 7

Part 5 — A short explanation of a long hiatus and a description of events thereafter

Back in New England, restaurateur Antony Parcheesi spied the Meteor one Saturday morning while watching cartoons. He remembered the schooner fondly from his youth... a time when he worked the docks helping Captain Sprat shovel fresh krill into the wooden hoggers. Tracking down the Meteor Tony was saddened to discover that the little schooner was about to be broken up. Without a second thought he decided to buy her and, sparing no expense, brought the Meteor home to Boston.

For nearly forty years the Meteor was a floating attraction at Antony’s Pier 7, a popular clam joint built on a converted barge. Then, in late autumn of 1986, a pretty close to perfect storm swept the Eastern Seaboard. Subjected to wild wind and wave the restaurant sank, but the Meteor, rather than get dragged down with the barge, parted her lines and sailed off under bare poles.

With Providence once again at the helm, the schooner made it to sea, ultimately coming to rest two hundred miles south in the soft sands of New York's Brighton Beach. When the storm had cleared she was spied at daybreak by a young, adventurous opportunist and Brooklyn native, Neal Parker. He instantly fell in love with the schooner and, wasting no time, got the vessel floated off before anyone else could claim her.

Back in New England, restaurateur Antony Parcheesi spied the Meteor one Saturday morning while watching cartoons. He remembered the schooner fondly from his youth... a time when he worked the docks helping Captain Sprat shovel fresh krill into the wooden hoggers. Tracking down the Meteor Tony was saddened to discover that the little schooner was about to be broken up. Without a second thought he decided to buy her and, sparing no expense, brought the Meteor home to Boston.

For nearly forty years the Meteor was a floating attraction at Antony’s Pier 7, a popular clam joint built on a converted barge. Then, in late autumn of 1986, a pretty close to perfect storm swept the Eastern Seaboard. Subjected to wild wind and wave the restaurant sank, but the Meteor, rather than get dragged down with the barge, parted her lines and sailed off under bare poles.

With Providence once again at the helm, the schooner made it to sea, ultimately coming to rest two hundred miles south in the soft sands of New York's Brighton Beach. When the storm had cleared she was spied at daybreak by a young, adventurous opportunist and Brooklyn native, Neal Parker. He instantly fell in love with the schooner and, wasting no time, got the vessel floated off before anyone else could claim her.

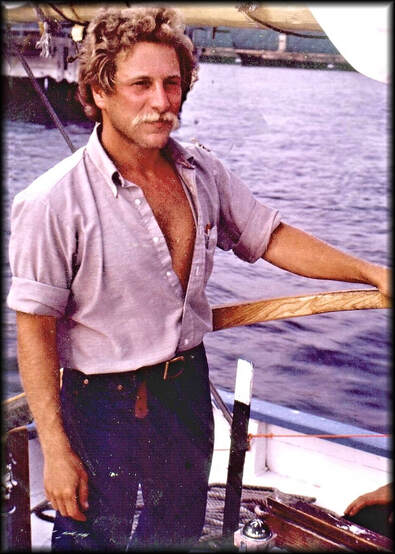

Captain Neal Parker at the helm poses for the Daily Post Times at the start of his Historic East River Adventure.

Captain Neal Parker at the helm poses for the Daily Post Times at the start of his Historic East River Adventure.

Part 6 — The Long Voyage Home

Parker had now realized the first part of his lifelong dream. A free boat. With it he could pursue the second part of that same dream, a voyage of discovery. It would be an undertaking which, inexplicably, no one in history had ever tried before. Parker was determined to find the source of the East River.

With the Meteor provisioned, Parker pulled anchor and set out. Using a decades-old Texaco map that he found on board, Parker hung a sharp right after the roller coasters, then steered northward through the expansive Verrazano Narrows. The young skipper kept a keen lookout as he passed under the great bridge towards the legendary Gowanus Canal. Years later Parker wrote in his autobiography:[7]

“...in that moment I felt like Odysseus of old and imagined I could hear the call of the Sirens.”

He went on to state:

“...their song was near impossible to resist but, not wishing to die,

I held my course.”

With a five-knot current at her back the Meteor was making a solid six knots. Traveling at such clip it wasn’t long before Captain Parker sighted Governor’s Island at the mouth of the East River. Taking the tide up Buttermilk Channel, Parker braced himself. Soon he was to traverse a dangerous, narrow, unforgiving passage of rampant eddies and tidal whirlpools... a navigational maelstrom where many a vessel had been forced back or wrecked... but the Meteor’s brave skipper held true and, without misfortune, Hell’s Gate was soon well astern.

Aided by a stiff autumn wind Parker kept his easting. When a month had passed and the Meteor had circumnavigated Long Island eleven times the young skipper finally understood why no one had ever discovered the source of the East River.

It was then, with provisions nearly depleted, that Parker rounded Montauk for the last time and, easing sail, laid a course for Maine. He had heard it was the place to bring an aging schooner, a refuge where old vessels thrived and the last frontier where you could register a boat without a title and a whole lot of paperwork.[8]

Captain Parker’s discovery of the Meteor proved to be fortuitous for both boat and man. The young mariner, without formal education and near penniless, decided to use the little schooner for taking summer visitors on sailing trips. He could charge gobs of money, knowing people would be delighted to sail along the beautiful rocky shores, past the romantic lighthouses of Penobscot Bay all the while listening to the cry of wild osprey and the incessant, endless, nonstop, ear-piercing, unrelenting screech of gulls.

On the days when the wind is light and guests don’t need to hold on for dear life, Parker, who is now an old salt himself, will invite folks to join him in the cockpit. There, if asked, he’ll gleefully share a completely fictitious account of the schooner Meteor while often inspired to add new material as the schooner sails along.

[7] As of this writing I Becomes A Sailor remains unpublished, as the author claims he has not decided on a suitable ending.

[8] The rules may have since changed. Before attempting to register a boat in Maine please check with state and local authorities... and children 13 and under must wear life jackets at all times... even in a car and at home or going potty.

Parker had now realized the first part of his lifelong dream. A free boat. With it he could pursue the second part of that same dream, a voyage of discovery. It would be an undertaking which, inexplicably, no one in history had ever tried before. Parker was determined to find the source of the East River.

With the Meteor provisioned, Parker pulled anchor and set out. Using a decades-old Texaco map that he found on board, Parker hung a sharp right after the roller coasters, then steered northward through the expansive Verrazano Narrows. The young skipper kept a keen lookout as he passed under the great bridge towards the legendary Gowanus Canal. Years later Parker wrote in his autobiography:[7]

“...in that moment I felt like Odysseus of old and imagined I could hear the call of the Sirens.”

He went on to state:

“...their song was near impossible to resist but, not wishing to die,

I held my course.”

With a five-knot current at her back the Meteor was making a solid six knots. Traveling at such clip it wasn’t long before Captain Parker sighted Governor’s Island at the mouth of the East River. Taking the tide up Buttermilk Channel, Parker braced himself. Soon he was to traverse a dangerous, narrow, unforgiving passage of rampant eddies and tidal whirlpools... a navigational maelstrom where many a vessel had been forced back or wrecked... but the Meteor’s brave skipper held true and, without misfortune, Hell’s Gate was soon well astern.

Aided by a stiff autumn wind Parker kept his easting. When a month had passed and the Meteor had circumnavigated Long Island eleven times the young skipper finally understood why no one had ever discovered the source of the East River.

It was then, with provisions nearly depleted, that Parker rounded Montauk for the last time and, easing sail, laid a course for Maine. He had heard it was the place to bring an aging schooner, a refuge where old vessels thrived and the last frontier where you could register a boat without a title and a whole lot of paperwork.[8]

Captain Parker’s discovery of the Meteor proved to be fortuitous for both boat and man. The young mariner, without formal education and near penniless, decided to use the little schooner for taking summer visitors on sailing trips. He could charge gobs of money, knowing people would be delighted to sail along the beautiful rocky shores, past the romantic lighthouses of Penobscot Bay all the while listening to the cry of wild osprey and the incessant, endless, nonstop, ear-piercing, unrelenting screech of gulls.

On the days when the wind is light and guests don’t need to hold on for dear life, Parker, who is now an old salt himself, will invite folks to join him in the cockpit. There, if asked, he’ll gleefully share a completely fictitious account of the schooner Meteor while often inspired to add new material as the schooner sails along.

[7] As of this writing I Becomes A Sailor remains unpublished, as the author claims he has not decided on a suitable ending.

[8] The rules may have since changed. Before attempting to register a boat in Maine please check with state and local authorities... and children 13 and under must wear life jackets at all times... even in a car and at home or going potty.